M is for Monsters:

M is for Monsters:We’ve mentioned the various four-color gargantua back at G. Now, let’s take a moment to consider the other monsters that menaced the comics world after the loosening of the Comics Code. Marvel tested the water with a living vampire (thus, technically not undead)—Morbius—first appearing in Amazing Spider-Man #101 (1971), but graduating into his own Adventure into Fear with #20 (1974).

After that the Big Two went after the famous monsters of filmland. Dracula went from villain to antihero in multiple Marvel mags starting with 1972's Tomb of Dracula. Marvel’s wolfman was the Werewolf by Night debuting in Marvel Spotlight vol. 1 #2 in 1972, but ultimately getting his own title. We got dueling Frankenstein’s Monsters in January, 1973—Marvel gave life to The Monster of Frankenstein, while DC nurtured the Spawn of Frankenstein in Phantom Stranger vol. 2 #23. The Living Mummy, who shambled through Supernatural Thrillers starting with #5 (1973), did genre double-duty as sort of blaxploitation and horror. The weakest of these celluloid reimaginings was probably Marvel’s Manphibian—a Gill-Man wannabe—from Legion of Monsters #1 (1975). A possibly film-inspired footnote (if we count German silent film—and you know I do) is the Golem, unearthed in Strange Tales vol. 1 #174 (1974), though of course the original Jewish folktale is the ultimate source.

There were also plenty of original monsters. Dueling swamp monsters rose from the muck in 1971 with Marvel’s Man-Thing and DC’s Swamp Thing. Marvel’s Scarecrow almost got his own series but instead emerged from a painting into Dead of Night #11. DC sent monsters into combat in World War II as the Creature Commandos. And what creature catalogue would be complete without acknowledging the ghosts, ghoulies, and assorted grotesques that graced the pages of the various horror anthology comics throughout the era?

N is for New Gods:

N is for New Gods:"There came a time when the Old Gods died…" the narrator tells us in Kirby’s New Gods vol. 1 #1 (1971). Maybe reports of the old gods’ deaths were premature. Instead, the Norse and Greek Pantheon mainstays of comics since the Golden Age were being forced to share the increasingly crowed heavens. Marvel added the Egyptian, Chinese, Indian, and Slavic gods, among others, as the gods of Earth formed sort of a United Pantheons to strategize for the return of the Celestials. This led to the creation of the Young Gods in Thor vol. 1 #203 (1972) who were intended to exemplify the best of humanity. Marvel also took inspiration from the pulps, borrowing Set wholesale(wholescale?) from Robert E. Howard, and the inspirations for tentacled horror, Shuma-Gorath, and the Elder God, Chthon, from HP Lovecraft.

But those are all old mythologies, new to comics though they maybe be. Jack Kirby wanted to give us something brand new—and he did it in his so-called "Fourth World" spanning multiple titles, but centering on the titular New Gods. The Manichean struggle between Apokolips and New Genesis has gone on for over a decade after their creator's death, and—Final Crisis(es) aside—will probably go on for sometime longer. Kirby created another pantheon of new gods (but these masqueraded as old gods) in the von Daniken inspired Eternals in 1976. The Eternals were created by yet another group of new gods—the enigmatic gang of giant, weirdly armored super-aliens called the Celestials, who liked to judge things Old Testament-style. Jim Starlin, taking inspiration from the Book of Kirby, brought forth his own new gods in Iron Man when he introduced Thanos (a Darkseid stand-in) who was born of a hereto unknown branch of the Titans of Greek myth, though they were later retconned to be a splinter group of Eternals.

O is for Out-there Outfits:

O is for Out-there Outfits:Comic book costumes have never been what you would call demure or conservative, but in the Bronze Age comic couture went to a whole new level. It’s cool that Luke Cage was secure enough in his masculinity to wear a canary yellow Pirate shirt, but are we to assume the metal head- and wrist-bands, and chain-link sash are a statement about the place of the black man in 70s America—or a case of accessories making the outfit? Do the psychedelic raccoon eyes of Dazzler, Kitty Pryde, and Marionette really hide their identities, or just get them noticed at the discotheque? And speaking of Dazzler, this fashion forward lady also sported mirrored roller skates, and a jumpsuit—excuse me, Parisian nightsuit. Another disco-victim was the Spider-Man villain Hypno-Hustler, who looks like he gave up a promising career with Parliament for a life of crime. So you don’t think I’m (just) picking on disco, I’ll push out onto the runway: Satana—in an oh-so European, precariously cutaway unitard and shaggy, fur boots assemble, followed by Red Sonja—in a Hyborian Age haute couture scale mail-kini.

Let’s not play favorites, though. DC had more than its share of questionable fashion statements. Supergirl did a lot of fashion don'ts, beginning in Adventure Comics vol. 1 #397 (1970), as she embarked on a series of reader designed costumes. She went through six costumes and an evening gown before settling on her outfit for the rest of the 70s: hot pants, a chocker, and a V-neck billowy-sleeved shirt. I blame those kids from the future she was hanging out with, ‘cause the Legion of Super-Heroes introduced Bronze Age readers to a brave new world of fashion with the 70s redesigns of Dave Cockrum, further (uh) refined by Mike Grell. Let's run the list: Extensive cutouts? Threatened wardrobe malfunction? High collars? High collar, no pants, and Peter Pan shoes? That’s a big, synthesized, computer-voice "AFFIRMATIVE" to all of the above. The prize for most out-there Legion outfit goes to Cosmic Boy's duds debuted in Superboy vol. 1 #215 (1976) which are best described as...well...uh—a black bustier, and gloves affair? That’s the best I can do, really. You’re just going to have to google it. In fact, Cosmic Boy may win the whole DC category, beating out swordswoman Starfire's green-dotted, cutout partial unitard, and Warlord supporting cast member Shakira's fur bikini with booties.

P is for President:

P is for President: The American President had appeared before the Bronze Age—most famous perhaps is Kennedy’s post-assassination appearance in Superman—but the push toward greater topicality in the Bronze Age had real (and fictional) presidents turning up more often. President as protagonist-in-chief had its highwater mark in the 1973-74 DC series Prez: First Teen President. Prez (both title and first name) Rickard dealt with the tough issues of his day—legless vampires, and Russian chess-player supervillians, for example. He also appointed a Native American, Eagle Free (complete with war bonnet and teepee), as head of the FBI, and his own mother, Martha, as VP. Compared to that, the term of alternate earth Kyle Richmond (the Squadron Supreme’s Nighthawk) is almost uneventful—except for possession by an alien intelligence leading to suspension of the Constitution, and subsequent conquest of the whole planet. I'd almost be willing to sit through the CSPAN coverage of the Congressional hearings after that one...

In the realm of presidents you might actually have studied in school, FDR got a retroactive role in the creation of the Justice Society of America in DC Special #29 (1977). In 1973, Richard Nixon was embroiled in Watergate; but in the pages of Captain America that same year, the nefarious Number One of the Secret Empire was implied to be the President under the hood (taking the "Tricky Dick" thing to a whole new level!)—just before he committed suicide in the White House.

Today I am pleased to present this interesting interview with veteran Artist

Today I am pleased to present this interesting interview with veteran Artist  There were a lot of companies in the 80's that you could submit samples to. Some rejected me, and some gave me work. I was one of the first American artists that worked for a British company when I did Sunrise for Harrier Comics in 1983. Most British artists came here, I did the opposite! Also, Grant Morrison had a back up story in it, so how weird is that?

There were a lot of companies in the 80's that you could submit samples to. Some rejected me, and some gave me work. I was one of the first American artists that worked for a British company when I did Sunrise for Harrier Comics in 1983. Most British artists came here, I did the opposite! Also, Grant Morrison had a back up story in it, so how weird is that?

As a rule…. When DC/Warner started making those straight to DVD movies…. I pretty much stayed away from them movies.

As a rule…. When DC/Warner started making those straight to DVD movies…. I pretty much stayed away from them movies.

Why could they not use the same Batman costumes in Batman Returns as in the first Batman film?? No they HAD to re-design it. And the costume in Batman Returns is not better then the one in Batman… it’s just slightly different.

Why could they not use the same Batman costumes in Batman Returns as in the first Batman film?? No they HAD to re-design it. And the costume in Batman Returns is not better then the one in Batman… it’s just slightly different.

Editor's Note: Today's Bronze Age Spotlight introduces a new writer to the Flashback Universe Team: Crom! Crom is a fiction and film writer for 2nd Culture, an IP creation company. Crom prefers the rocket launcher to the rail gun, Marvel to DC, and Classical to Post-modern. Crom is not a robot from the future, but we're not sure about his illegitimate offspring. You can learn more at his

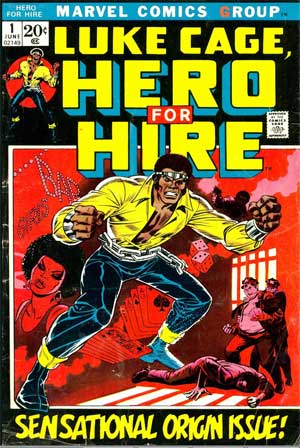

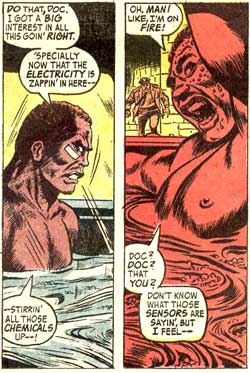

Editor's Note: Today's Bronze Age Spotlight introduces a new writer to the Flashback Universe Team: Crom! Crom is a fiction and film writer for 2nd Culture, an IP creation company. Crom prefers the rocket launcher to the rail gun, Marvel to DC, and Classical to Post-modern. Crom is not a robot from the future, but we're not sure about his illegitimate offspring. You can learn more at his  As it does with all comic book Doctors willing to subject human beings to experiments, things turn to the ridiculous... and for Lucas, add 30 CCs more racism.

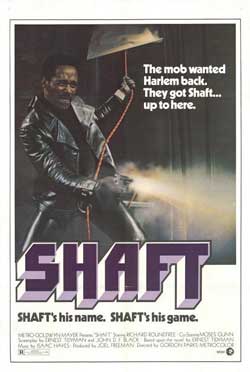

As it does with all comic book Doctors willing to subject human beings to experiments, things turn to the ridiculous... and for Lucas, add 30 CCs more racism. When 1972 hit, the blaxploitation movement was getting a full head of steam. The previous year had yielded two of the biggest films to make the scene: Sweet Sweetback’s Badass Song and the more well known Shaft. The Black badass had arrived. It was an archetype soon placed into mass production.

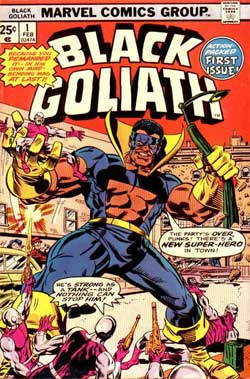

When 1972 hit, the blaxploitation movement was getting a full head of steam. The previous year had yielded two of the biggest films to make the scene: Sweet Sweetback’s Badass Song and the more well known Shaft. The Black badass had arrived. It was an archetype soon placed into mass production. However, let's give Marvel credit for publishing a comic with a black hero as the star and resisting the urge to use the word Black in the title. You KNOW they just wanted to call him Black Power Man. (Which is probably how he ended up with the name of Power Man later on.)

However, let's give Marvel credit for publishing a comic with a black hero as the star and resisting the urge to use the word Black in the title. You KNOW they just wanted to call him Black Power Man. (Which is probably how he ended up with the name of Power Man later on.) Editor's Note: Today I present a guest column by

Editor's Note: Today I present a guest column by  Over at DC Comics, Len Wein and artist Dick Dillon went one step farther. In Justice League of America #111 (Sept. 1974) they created the Injustice Gang of the World. A new “master villain” was introduced and gathered together the likes of Mirror Master, Scarecrow, Poison Ivy, the Tattooed Man, and Chronos (The seemingly staple of almost every villain team DC came up with at that time). Libra not only betrayed his team, but beat them and left them for the authorities to pick up. Strangely, this both disappointed me and excited me at the time. Maybe that is what they were aiming for. This was now offically the formula for super villain teams that seemed to work. This is what was making a great super villain team: Who will betray who?

Over at DC Comics, Len Wein and artist Dick Dillon went one step farther. In Justice League of America #111 (Sept. 1974) they created the Injustice Gang of the World. A new “master villain” was introduced and gathered together the likes of Mirror Master, Scarecrow, Poison Ivy, the Tattooed Man, and Chronos (The seemingly staple of almost every villain team DC came up with at that time). Libra not only betrayed his team, but beat them and left them for the authorities to pick up. Strangely, this both disappointed me and excited me at the time. Maybe that is what they were aiming for. This was now offically the formula for super villain teams that seemed to work. This is what was making a great super villain team: Who will betray who?

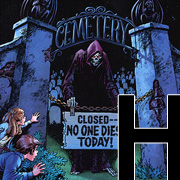

H is for horror hosts: Horror anthology comics having equally horrorific hosts is a tradition going back to 1950s EC comics' three so-called "GhouLunatics." The Comics Code had no room for horror framed by snarky comments and bad puns, so the hosts were out of work, except in TV tie-ins like the Twilight Zone, or non-Code approved magazines like Warren's Eerie and Creepy. But the Code loosened in the Bronze Age, and Cain became the "able [heh] care taker" of the House of Mystery in #175 (1968). The object of his fatricidal rage, Abel, moved into The House of Secrets in 1969. DC gave the (grave)moldering host-concept a makeover with the Mad Mod Witch in The Unexpected #108 (August 1968). Macbeth's Three Witches doubled toil and trouble at The Witching Hour (1969-1978). 1969 also saw the debut of Marvel's only hosted horror title, Tower of Shadows, which had not one, but two cemetery-themed emcees--Digger and Gravely P. Headstone.

H is for horror hosts: Horror anthology comics having equally horrorific hosts is a tradition going back to 1950s EC comics' three so-called "GhouLunatics." The Comics Code had no room for horror framed by snarky comments and bad puns, so the hosts were out of work, except in TV tie-ins like the Twilight Zone, or non-Code approved magazines like Warren's Eerie and Creepy. But the Code loosened in the Bronze Age, and Cain became the "able [heh] care taker" of the House of Mystery in #175 (1968). The object of his fatricidal rage, Abel, moved into The House of Secrets in 1969. DC gave the (grave)moldering host-concept a makeover with the Mad Mod Witch in The Unexpected #108 (August 1968). Macbeth's Three Witches doubled toil and trouble at The Witching Hour (1969-1978). 1969 also saw the debut of Marvel's only hosted horror title, Tower of Shadows, which had not one, but two cemetery-themed emcees--Digger and Gravely P. Headstone. I is for Implosion: Remember the awesome 70s Vixen series? How about that Green Team on-going? Well, what about Grell's DC series, Starslayer? No? That's because in this universe, they never happened. In the Bronze Age, DC and Marvel waged a war for dominance of the shrinking comics market. In 1975, they both seemed to have arrived at a plan of throwing as many concepts out as possible and seeing what stuck. Between 1975 and 1978, DC and Marvel brought out 100 new titles. DC published 57 of these in what house ads trumpeted as "The DC Explosion." The market didn't--or couldn't--respond in the way DC hoped. Titles were axed, and in late 1978 there was a four-color holocaust--31 titles were sent to comic book oblivion in that year alone. Claw was conquered, Firestorm extinguished, and the Doorway to Nightmare shut. No one welcomed Kotter back. This massacre became known as the DC Implosion. In many ways, this loss of wild creativity and innovation was the real crisis that ended the DC Bronze Age.

I is for Implosion: Remember the awesome 70s Vixen series? How about that Green Team on-going? Well, what about Grell's DC series, Starslayer? No? That's because in this universe, they never happened. In the Bronze Age, DC and Marvel waged a war for dominance of the shrinking comics market. In 1975, they both seemed to have arrived at a plan of throwing as many concepts out as possible and seeing what stuck. Between 1975 and 1978, DC and Marvel brought out 100 new titles. DC published 57 of these in what house ads trumpeted as "The DC Explosion." The market didn't--or couldn't--respond in the way DC hoped. Titles were axed, and in late 1978 there was a four-color holocaust--31 titles were sent to comic book oblivion in that year alone. Claw was conquered, Firestorm extinguished, and the Doorway to Nightmare shut. No one welcomed Kotter back. This massacre became known as the DC Implosion. In many ways, this loss of wild creativity and innovation was the real crisis that ended the DC Bronze Age. J is for Junkie: In 1971, Stan Lee took on the Comic Code Authority to publish a story showing the negative effects of drug use. Amazing Spider-Man #96 (sporting the lurid cover blurb "The Last Fatal Trip!") had Harry Osborne act out an LSD cliché, but it led to a change in the Comics Code. The door was open for the Bronze Age to show the sensationalistic horrors of addiction. The unfortunately named Speedy became a heroin addict (and a rock musician) in a socially relevant story arc in Green Lantern #85-88 (1971). In a 1979 Iron Man story arc, cocktail-swilling Tony Stark battled his own "Demon in a Bottle." Addiction could also provide costumed motivation, like in the case of the Black Spider, former small-time crook and heroin addict, who waged a murderous war on the narcotics trade, before running afoul of Batman in Detective Comics #463 (1976). Late Bronze-Agers Cloak and Dagger weren't addicts, true, but they did get their powers through being unwilling guinea pigs in a nefarious plot to perfect synthetic heroin. Sorry, Mr. O'Neil: maybe the snowbird does fly--at least in the Bronze Age.

J is for Junkie: In 1971, Stan Lee took on the Comic Code Authority to publish a story showing the negative effects of drug use. Amazing Spider-Man #96 (sporting the lurid cover blurb "The Last Fatal Trip!") had Harry Osborne act out an LSD cliché, but it led to a change in the Comics Code. The door was open for the Bronze Age to show the sensationalistic horrors of addiction. The unfortunately named Speedy became a heroin addict (and a rock musician) in a socially relevant story arc in Green Lantern #85-88 (1971). In a 1979 Iron Man story arc, cocktail-swilling Tony Stark battled his own "Demon in a Bottle." Addiction could also provide costumed motivation, like in the case of the Black Spider, former small-time crook and heroin addict, who waged a murderous war on the narcotics trade, before running afoul of Batman in Detective Comics #463 (1976). Late Bronze-Agers Cloak and Dagger weren't addicts, true, but they did get their powers through being unwilling guinea pigs in a nefarious plot to perfect synthetic heroin. Sorry, Mr. O'Neil: maybe the snowbird does fly--at least in the Bronze Age. K is for Kung Fu: In the early seventies, everybody was kung-fu fighting as eastern martial arts mania caught pop culture in its grip. In 1973, the one-two punch of Bruce Lee's Enter the Dragon, and the Kung Fu TV series, got Marvel in the fray with Shang-Chi, Master of Kung Fu, debuting in Marvel Special Edition #15. The character was such a hit that the title was rechristened The Hands of Shang-Chi: Master of Kung Fu with #17 in 1974. That year the dojo got crowded with Marvel's Iron Fist, and the Sons of the Tiger, both of whom would make appearances in the black and white magazine Deadly Hands of Kung Fu. Jim Dennis (a combined pseudonym for Denny O'Neil and Jim Berry) produced a kung fu novel in '74, titled Dragon Fists--which served as a "backdoor pilot" for DC's entry into the arena with Richard Dragon, Kung Fu Fighter (1975). That same year, Charlton invited fans to the House of Yang, which was a spin-off of their "don't call it Kung Fu: the Comic" 1973 series Yang. DC emphasized the "karate" in the name of the some-time Legionnaire, Karate Kid in his high-kicking solo-series starting in1976. By the end of the seventies, virtually all of those characters were in limbo, "superherofied", or settled into mentor/trainer roles. Exit the Dragon.

K is for Kung Fu: In the early seventies, everybody was kung-fu fighting as eastern martial arts mania caught pop culture in its grip. In 1973, the one-two punch of Bruce Lee's Enter the Dragon, and the Kung Fu TV series, got Marvel in the fray with Shang-Chi, Master of Kung Fu, debuting in Marvel Special Edition #15. The character was such a hit that the title was rechristened The Hands of Shang-Chi: Master of Kung Fu with #17 in 1974. That year the dojo got crowded with Marvel's Iron Fist, and the Sons of the Tiger, both of whom would make appearances in the black and white magazine Deadly Hands of Kung Fu. Jim Dennis (a combined pseudonym for Denny O'Neil and Jim Berry) produced a kung fu novel in '74, titled Dragon Fists--which served as a "backdoor pilot" for DC's entry into the arena with Richard Dragon, Kung Fu Fighter (1975). That same year, Charlton invited fans to the House of Yang, which was a spin-off of their "don't call it Kung Fu: the Comic" 1973 series Yang. DC emphasized the "karate" in the name of the some-time Legionnaire, Karate Kid in his high-kicking solo-series starting in1976. By the end of the seventies, virtually all of those characters were in limbo, "superherofied", or settled into mentor/trainer roles. Exit the Dragon. L is for Lost Worlds: Let's get our terminology straight. We're not talking about otherworldly fantasylands (like Gemworld), forgotten prehistories (like Conan's Hyborian Age, or mythological realms (like Asgard). Instead we're looking at the Bronze Age echoes of Arthur Conan Doyle's Maple White Land, the titular Lost World.

L is for Lost Worlds: Let's get our terminology straight. We're not talking about otherworldly fantasylands (like Gemworld), forgotten prehistories (like Conan's Hyborian Age, or mythological realms (like Asgard). Instead we're looking at the Bronze Age echoes of Arthur Conan Doyle's Maple White Land, the titular Lost World.