Thursday, July 17, 2025

Paperback Flashback: Warrior of Llarn

Wednesday, July 9, 2025

Jame Gunn's Superman

Last night, I attended a special showing of James Gunn's Superman. My short review is: I liked it a lot. I think it's the best Superman movie ever (with the caveat that it likely wouldn't have been made without an existing tradition of Superman films to build and comment upon), and one of the best superhero movies period.

I was a bit worried, honestly, when I heard Gunn was going to helm this one. I've enjoyed his previous films, but they often engage in a level and type of humor that while fine on an individual film level, I have come to like less when it's the standard for superhero films. There's often not a lot of space in the movies between having fun with superheroes and making fun of them.

Also, as specifics for this film became to come out, I had other concerns. It seemed like it was overstuffed, like Gunn was trying to jumpstart an entire universe with one movie. That sort of ambition has proved hubris for superhero movies before, I feel like. The Marvel Cinematic Universe, I think most everyone would agree, seems at times to be spewing out product solely to point to future products.

Happily, my fears weren't realized. The film has humor, yes, but it isn't farcical or even particularly quippy in the tired manner of CMU films. It does eschew any of the reverence or perhaps mythic tone that has been a part of Superman's cinematic portrayals since the first Donner film--to the detriment, I think, of later films like Superman Returns or Man of Steel. This film is lighter, definitely, but critics of the "darkness" of the Snyder films should reckon with this films inclusion of government sanctioned extralegal detention, torture, Lex Luthor murdering an innocent man to coerce Superman, an extralegal execution by a superhero, and a shocking (well, as shocking as something that was foreshadowed with the subtlety of a flare) reveal about Jor-El and Lara.

Through this all, Superman, however, stays good and strangely innocent. This is the character at his most "Blue Boy Scout." It's to a degree not seen, perhaps, since the Superfriends. Gunn seems to have gotten an aspect of the pre-Crisis Superman (perhaps from Morrison's All-Star Superman) that isn't much talked about where Superman suffers indignity and hurt to solve problems in the name of not resorting to violence or at least to minimize violence before he acts. It's a thing that most sets his stories apart from Marvel Comics stories or even his fellow headliner at DC, Batman. While it likely started as a means to not have stories end too quickly through use of amazing power ultimately sort of became a character trait.

The film is perhaps objectively a bit of a too rich superhero confection, but its kind of in media res plotting makes things move along so that it's not ponderous. Further, the inclusion of multiple other heroes doesn't seem to be merely to build a universe. The narrative needs those other heroes so we can see Superman inspiring others to be better, and we can feel the limits of his personal abilities. Even Superman sometimes needs a friend.

There are things I didn't care for. The Kents are rural caricatures in a way they've never seen before and that's distracting and unnecessary. It might be a mistake to have Lois raise very good points about the unilateral use of force in complicated geopolitical situations only to ignore them, or perhaps imply it's okay 'cause Superman's really, really good.

But dodging ethical questions and realistic implications has a long history in comics, so I can't get too upset about it here. Questionable portrayals of the Kents are hardly new to Superman media.

Overall, these feel like talking about the icing. The cake is really good.

Tuesday, July 1, 2025

Jim Shooter

As I'm sure you know, Jim Shooter passed away this week at the age of 73. While Shooter got his start at a wunderkind writer for DC in the 1960s on stories with the Legion of Super-Heroes, it is his tenure as Marvel's Editor-in-Chief where he probably made his biggest mark. Certainly, that is where comics reader of my generation will most remember him.

No doubt due to my age at time, but the Shooter work most dear to my heart is Secret Wars. Secret Wars II, well, not so much.

Though I was a latecomer to it, I enjoyed his work with Bob Layton, Don Perlin, and Barry Windsor-Smith on the first year or so of Solar, Man of the Atom. It was both a solid addition to the post-Miracle Man and Watchmen wave of superhero deconstruction and a second attempt at the "realistic supers" approach he tried with the New Universe.

But these are just the ones that stand out for me. Shooter wrote a lot of comics, and no doubt helped shape others (for good and ill) to their final form as an editor. He had a big impact on the industry.

Thursday, June 26, 2025

Attack of the (Star Wars) Comics Clones

Empire? A sinister Corporation that controls Earth

Rebels? Sort of, though the protagonists start out forced to work for the Corporation

The Force? There's an "Entity" and a cosmic battle between good and evil

Analogs? Donovan Flint, the primary protagonist, is a Han Solo type with a mustache prefiguring Lando's.

Notes: If Star Hunters is indeed Star Wars inspired, its a very early example. The series hit the stands in June of 1977--on a few days over a month after Star Wars was released.

Micronauts (1979)

Empire? A usurpation of the monarchy of Homeworld.

Rebels? Actually previous rulers and loyalists; a mix of humans, humanoids, and robots.

The Force? The Enigma Force, in fact.

Analogs? Baron Karza is a black armored villain like Vader; Marionette is a can-do Princess; Biotron and Microtron are a humanoid robot and a squatter, less humanoid pairing like Threepio and Artoo.

Empire? The Zygoteans, who have concurred most of the galaxy.

Rebels? A disparate band from various worlds out to end the Zygotean menace.

The Force? There's Starlin cosmicness.

Analogs? Aknaton is an old mystic who know's he's going to die a la Obi-Wan. He picks up Dreadstar on a backwater planet and gets him an energy sword.

Dreadstar (1982)

Empire? Two! The Monarchy and the Instrumentality.

Rebels? Yep. A band of humans and aliens out to defeat the Monarchy and the Instrumentality.

The Force? Magic and psychic abilities.

Analogs? Dreadstar still has than energy sword; Oedi is a farm boy (cat) like Luke; Syzygy is a mystic mentor like Kenobi; Lord High Papal is like Vader and Palpatine in one.

Notes: Dreadstar is a continuation of the story from Metamorphosis Odyssey.

Atari Force (1984)

Empire? Nope.

Rebels? Not especially.

The Force? Some characters have special powers.

Analogs? Tempest is a blond kid with a special power and a difficult relationship with his father sort of like Luke. There are a lot of aliens in the series, so there's a "cantina scene" vibe; Blackjak is a Han Solo-esque rogue. Dark Destroyer is likely Vader-inspired, appearance-wise.

Notes: This series sequel to the original series DC did for Atari, taking place about 25 years later. The first series is not very Star Wars-y.

Thursday, June 19, 2025

Neon Visions

The mysterious and pervasive algorithms of the internet offered me this book the other day: Neon Visions: The Comics of Howard Chaykin. I'm interested in checking it out. Though I'm not familiar with the author, I agree with his contention that Chaykin's contributions to the field haven't been analyzed with the same sort of detail afforded other creators.

Once I got around to reading it, I'll report back.

Thursday, June 5, 2025

Some Collections I Enjoyed

Sometimes, I finally get around to reading some stuff from decades back that's new (at least in part) to me. Here were my thoughts on a couple of things:

Incredible Hulk Epic Collection: Crisis on Counter-Earth: I hate that the Big Two don't number a lot of collections these days, but if it matters this is volume 6 of the Hulk Epic Collections, apparently. These are stories from the early 70s, written by Englehart and Thomas and drawn by Trimpe and they are crazy. The Hulk wanders from one situation (and fight) to another, often running into people he knows no matter where he is. The Marvel universe seems really small!

It opens with Hulk returning to Earth after a sojourn in Jarella's microverse world, which he accidentally kicked out of orbit when he grew big again. He's briefly reunited with some of his supporting cast, but then he's attacked by the Rhino being mind-controlled by the Leader. He pursues Leader/Rhino into a spacecraft and keeps trying to fight him as the ship veers off course and takes them to Counter-Earth. They are there for 1 issue and get involved in conflict with factions of New Men, before grabbing a rocket back to regular Earth. There, Hulk goes looking for Betty who's marrying Talbot. Ross sends Abomination to fight him, but Hulk prevails, and Abomination has a breakdown over the fact he had ben unconscious for 2 years (since his last appearance where Hulk punched him out of space). And all this isn't even halfway! The Hulk goes to Counter-Earth again before it's all over and bears witness to the death and resurrection of Adam Warlock.

This the sort of flying by the seat of the pants comics' storytelling we don't get in this age of decompression.

Solar, Man of the Atom (1991): Valiant wasn't on my radar when it started and by the time it was it was the darling of Wizard. I was skeptical and avoided it. So, 30 plus years later I'm getting around to reading it's second title. And I'm actually pretty impressed.

Shooter is definitely still cogitating on the concerns that led to the conception of the New Universe. Valiant is realistic superheroes. Where for Moore "realistic" means a whole lot of sexual fetishes, for Shooter it means them having to deal with problems like the unexpected difficulties of flying (it's like a motorcycle but worse) or what to do if your powers keep destroying your clothes. (Maybe some sexual fetishes, too, but they show up less.) Shooter's protagonists in this realistic mode, from Star Brand to Solar, have a hard time figuring out how to do the superhero thing--the sort of stuff that somehow just seems to happen for people when they get powers in most comics.

Shooter's protagonist, Phil Seleski, definitely can't get things right. He gave himself powers Dr. Manhattan-style in a fusion mishap, but then something bad happened that resulted in the deaths of a lot of people. So, now he's back in time trying to stop that. Maybe he'll kill his past self--but then he accidentally creates his childhood superhero fav Dr. Solar from parts of his psyche, and now that guy is convinced future Phil is a super-villain. Which, in a way, he sort of is.

Eventually, all of this resolves into more standard stuff, but it's a pretty interesting origin, perhaps given additional resonance by the sense of foreboding Windsor-Smith's art creates with the flashback backstory--though maybe this is only for me since I last read his stuff in Monster. For some reason, comics in the 80s and early 90s at least tend to do interesting things with nuclear test related heroes: Dr. Manhattan, the Bates/Weisman/Broderick Captain Atom, and this. Firestorm is perhaps the odd man out.

Thursday, May 29, 2025

Blackstar's Planet Sagar

Recently, I revisited the 13 episodes of the 1981 Filmation Saturday morning animated series, Blackstar. Jason and I watched an episode of Blackstar back in our Classic TV Flashback series. Watching most of the episodes, I feel like I came away with a good sense of the worldbuilding that was (or wasn't) being done to develop the planet Sagar as a fictional place. And I noticed some interesting details.

|

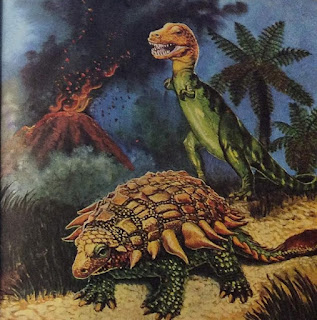

| Illustration from the Dinosaurs Little Golden Book |