"Know, O Prince, that between the years when the oceans drank Atlantis and the gleaming cities, and the years of the rise of the sons of Aryas, there was an age undreamed of, when shining kingdoms lay spread across the world like blue mantles beneath the stars…Hither came Conan the Cimmerian, black-haired, sullen-eyed, sword in hand, a thief, a reaver, a slayer, with gigantic melancholies and gigantic mirth, to tread the jeweled thrones of the Earth under his sandaled feet."

"Know, O Prince, that between the years when the oceans drank Atlantis and the gleaming cities, and the years of the rise of the sons of Aryas, there was an age undreamed of, when shining kingdoms lay spread across the world like blue mantles beneath the stars…Hither came Conan the Cimmerian, black-haired, sullen-eyed, sword in hand, a thief, a reaver, a slayer, with gigantic melancholies and gigantic mirth, to tread the jeweled thrones of the Earth under his sandaled feet."- The Nemedian Chronicles

Robert E. Howard, “The Phoenix in the Sword”

In 1970, Conan* came to Marvel comics, and by some reckoning, brought the whole of the Bronze Age with him. In the years that followed, other swordsman and thieves and various treaders of bejeweled thrones, would follow on Conan’s sandaled heels. They would be visitors from another time—another world—in more ways than one. The four-color world of superheroes would collide with the realm of Sword & Sorcery, a literary sub-genre born in what Lin Carter called “the sleazy, gaudy, glorious golden age of the pulps.”

So come with us now, back to the Bronze Age, where--in the Roy Thomas penned words of

Conan the Barbarian #1—“a man’s life was worth no more than the strength of his sword-arm!”

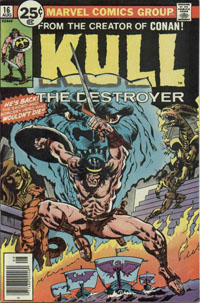

“THE MOST SAVAGE HEROES OF ALL!” Kull

KullRobert E. Howard’s Conan was the first literary sword and sorcery character to make it into comics, but he wasn’t the first sword and sorcery character. Conan made his debut in the December 1932 issue of

Weird Tales in a story titled “The Phoenix on the Sword.” This story takes place late in Conan’s life, when he’s king of Aquilonia. It seems a strange place to begin chronicling the barbarian wanderer’s adventures, given the distinct lack of wandering and the decreased levels of barbarism, but this beginning seems to have come by accident. Conan debuted in a story Howard rewrote from a story he had been unable to sell featuring an entirely different character. The original story was “By This Axe I Rule!” and the original hero was Kull. It was Kull, debuting in

Weird Tales August 1929 with “The Shadow Kingdom,” who is often considered the first sword and sorcery hero.

Only two Kull stories were published during Howard’s lifetime, though others have made it into print in collections since. Like Conan, Kull’s a barbarian that winds up winning a kingdom. Unlike Conan, the majority of Kull’s adventures deal with his life

after becoming king, and mainly center around how heavy the head is that wears the crown. Kull’s a more philosophical and introspective character than Conan—which may explain why he’s never been as popular.

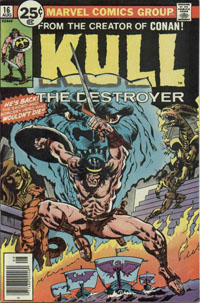

He’s a (relative) latecomer to comics, too. He first appeared in 1971 in Marvel’s

Kull the Conqueror, then a succession of two more short lived series of that same title from 1971 to 1985. He also starred in a short-lived, black and white magazine

Kull and the Barbarians (which sounds like a gothabilly band, doesn’t it?) in 1975, and made some crossover appearances with Conan in

Savage Sword of Conan. After years of quiet repose, King Kull loosed his blade again, this time for Dark Horse, beginning in 2008.

You just can’t keep a good barbarian down.

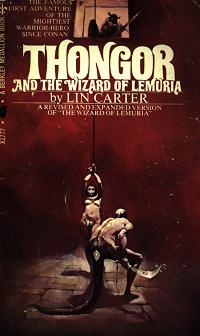

Thongor

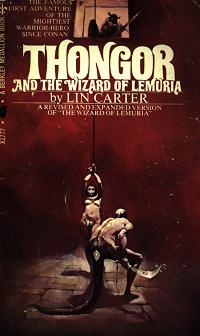

ThongorNot only wasn’t Conan the first sword and sorcery character, he almost wasn’t the first to make the leap to comics. Roy Thomas, tasked by Martin Goodman with bringing sword and sorcery to Marvel, had assumed Conan would be too expensive. As he relates in his essay in

The Chronicles of Conan Volume One (Dark Horse), he had initially pursued the first sword and sorcery character he had gotten into—Lin Carter’s Thongor of Lemuria.

The Thongor novels were a canny attempt by serial pasticher Lin Carter to combine two of his passions in one. To wit: Thongor--Northern Barbarian (remember Cimmerians? Like them) who adventured in a pseudo-prehistoric milieu (the Hyborian—uh,

Lemurian Age) but one which included city-states, airships, and invented flora and fauna (like Barsoom, or Amtor, or—well, you get the idea). In other words, they were Conan if written by Burroughs, or Howard doing planetary romance (which he actually did once, but that’s another story). Thongor swung his first sword in

The Wizard of Lemuria (1965).

Roy Thomas and Stan Lee figured the younger, less established Carter would cut a deal for less. And apparently, Stan thought “Thongor” sounded more “comic book”—and he has a point.

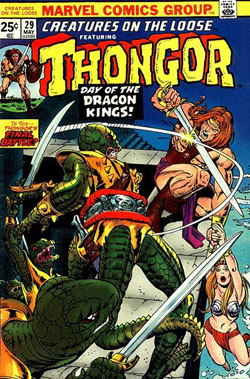

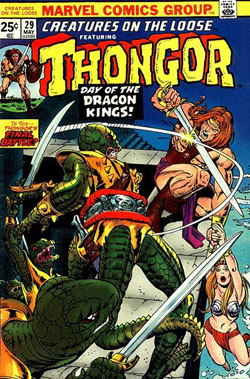

Such was not to be. Due to the vagaries of negotiation, Conan came through, and Thongor would sit on the sidelines until March 1973 with

Creatures on the Loose #23, where he would begin flexing mighty thews and generally behaving in a Conan-esque manner. Ravenhaired Thongor became a red-head after a couple of appearances, perhaps to distance him visually from his barbaric forebearer. Only, presumably, his hair-dresser knows for sure. Thongor battled monsters and foul sorcery until

Creatures on the Loose #29 (1974), when he lost the book to Man-Wolf. Several of his appearances were written by George Alec Effinger, whose 1986 cyberpunk novel,

When Gravity Fails, won both the Hugo and Nebula awards. Gardner Fox, with a long history of comics work and sword and sorcery (with

his barbarian, Kothar) would work on the run as well.

Thongor is obscure today, but he had shining moment of popularity (apparently) in the seventies. Lin Carter relates in

Imaginary Worlds, that a Thongor musical was in the offing, though I’m unsure if it was ever actually performed.

A Lin Carter website tells of a Thongor movie in production that was reported in

Starlog #15, apparently from the same cinematic titans that brought us the Doug McClure (and Caroline Munro!) vehicle

The Land that Time Forgot.

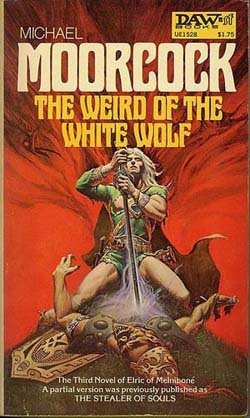

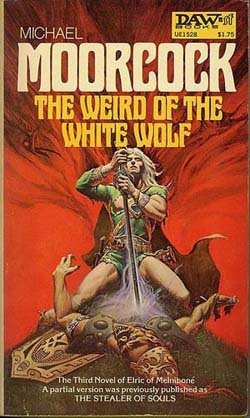

Elric

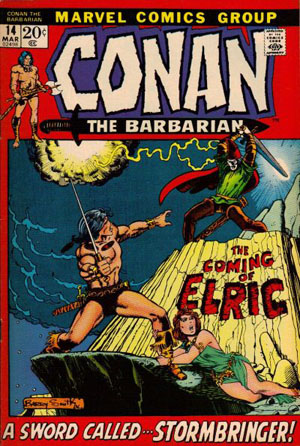

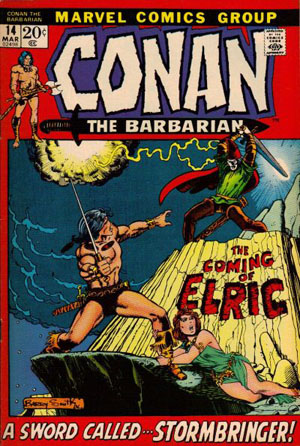

ElricL. Sprague De Camp, pasticher-in-chief, and his aide—uh—de camp, Lin Carter, had been adapting Howard’s non-Conan yarns into Conan stories to feed the maw of the Lancer Conan paperback series. Thomas had copied that approach in the comics, but expanded it to the adaptation of even non-Howard stories into Conan stories. In March 1972, he’d port over another character into Conan’s world—aided and abetted by that character’s creator. The two-part story beginning in

Conan #14 (“A Sword Called Stormbringer!”) adapted the original thin, white duke, Elric of Melnibone, in the Mighty Marvel Manner. Conan and Elric team up against Xiombarg, the Queen of Chaos, burrowed from the chronicles of Corum, another of Moorcock’s fantasy series.

Elric, albino prince and sort of anti-Conan armed with the don’t-call-it-a-phallic-symbol sword Stormbringer, is the creation of Michael Moorcock, and first appeared in literary form in the 1961 novella, “The Dreaming City.” His story continues to this day, the most recent novel having been published in 2005.

This Marvel Team-Up-esque two-parter wasn’t Elric’s only foray into comics. French artist Philippe Druillet of

Metal Hurlant fame, produced an unauthorized Elric graphic novel in the late sixties. Later, the “Dreaming City” was adapted as a Marvel (Epic) graphic novel by P. Craig Russell and Roy Thomas. Since the end of the Bronze Age, Elric has periodically raised his runesword in comics from First, Dark Horse, and DC.

BrakOne of the writers who provide more Conan comics material was John Jakes. Before he became forever linked with Patrick Swayze (at least in my mind) by the TV movie adaptation of his 80’s best-seller historical saga, Jakes wrote some Conan-inspired tales of sword-swinging adventure. His barbarian hero was blonde with a braided ponytail, named Brak. Brak first appeared in “Devils in the Walls” in the May 1963 issue of

Fantastic. He went on to star in a series of novels beginning in 1968 with

Brak the Barbarian. In 1982, Jakes’ second successful historical fiction series,

North and South began, and Brak has been seen no more.

Jakes first foray into comics was without his creation. He wrote the plot that became

Conan the Barbarian #13, “Web of the Spider-God” (January 1972). Exactly a year later, Brak debuted in the second issue of the horror anthology

Chamber of Chills. This story was reprinted in the black and white

Savage Tales (vol. 1) #4 (July, 1974), whose cover promised “THE MOST SAVAGE HEROES OF ALL.” Brak went on to do battle with the minions of evil, god-thing Yob-Haggoth, in his quest to reach Khurdisan the Golden and the high life, for just two more stories in

Savage Tales (issues 7 and 8) before disappearing into the mists of Bronze Age legendry. Brak never even got a cover appearance, most of those having been hogged by Ka-Zar.

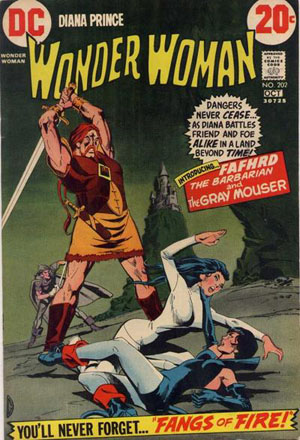

“TWO SOUGHT ADVENTURE”“

At least we have something in common!—we’re all three crooks!”

~ Catwoman (to Fafhrd and Gray Mouser)

Wonder Woman #202 (1972)

Perhaps it was because DC didn’t have the works of Robert E. Howard to fall back on, or maybe it was a reluctance to delve into this sort of material, but for whatever reason, they didn’t adapt as many literary sword and sorcery characters as Marvel.

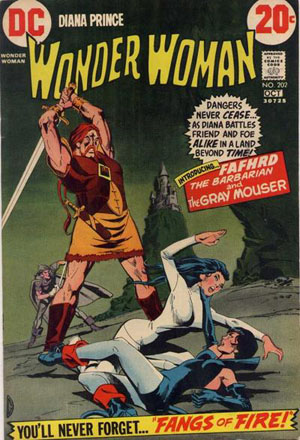

When they did, at least they got two for the price of one—Fritz Leiber’s sword and sorcery duo, Fafhrd and Gray Mouser.

Fafhrd and Gray Mouser’s prose debut was in

Unknown magazine in “the Year of the Behemoth, the Month of the Hedgehog, the Day of the Toad”—well,

in story, at least. In our world we may reckon that as August 1939. Leiber chronicled the twain’s adventures off and on from that story until 1988’s “The Mouser Goes Below”—a longer span than the entire life of Robert E. Howard. Fafhrd was a Northern barbarian from Cold Corner, and Gray Mouser was a thief and one-time sorcerer’s apprentice from the urban South. They met in decadent Lankhmar, “City of the Seven Score Thousand Smokes,” and became lifelong friends and companions in (mis)adventure.

When Fafhrd and Gray Mouser came to comics, they did so in an unlikely place. They first appeared on the last panel of Wonder Woman #201, during her powerless, kung-fu-fighting, Diana Prince era. Issue 202 has them teaming up with Wonder Woman, her

sifu I-Ching, and Catwoman, to thwart a wizard and save Jonny Double who’s trapped inside a mystic gem. In the words of Bart Simpson: “

You can’t make this stuff up!”

The issue was written by New Wave science fiction luminary, Samuel Delany. Highlights include Fafhrd backhanding Diana, and Mouser and Catwoman having a totem-appropriate face-off, before they all decide to join forces. This all serves as a “backdoor pilot” for the twain’s run in the bimonthly

Sword of Sorcery seriespremiering in 1973. It only ran for five issues, but featured original stories and adaptations, most scripted by Denny O’Neil (except for one by George Alec Effinger), and featuring art by Howard Chaykin, Walter Simonson, and Jim Starlin.

Fafhrd and Gray Mouser vanished from DC at the cancellation of

Sword of Sorcery. The two were next sighted at a different company in the 1991 Epic limited series which reunited them with Howard Chaykin, who scripted adaptations of Leiber’s tales. All issues featured evocative art by Mike Mignola.

“Let teachers and priests and philosophers brood over questions of reality and illusion. I know this: if life is illusion, then I am no less an illusion and being thus, the illusion is real to me. I live, I burn with life, I love, I slay, and am content."~ Conan

“Queen of the Black Coast” Robert E. Howard

Sword and Sorcery comics did good business in the Bronze Age, both with the licensed characters above, and original creations like Arak, Wulf, Claw, Ironjaw, and the Warlord. It was a true Golden Age for comic book sword-swinging!

Today, Robert E. Howard properties are still appearing in comics, mostly from Dark Horse. Image has given us a line inspired by some of Frank Frazetta’s great sword and sorcery-inspired paintings. Marvel and DC, on the other hand, have concentrated on the mainstream superheroes that are their bread and butter; most of their sword and sorcery creations stalk only the back issue bins.

These things go in cycles, surely. Maybe one of these days will see Karl Edward Wagner’s Kane, or perhaps the outré exploits of Michael Shea’s Nifft the Lean., realized on the comics page.

Until then…maybe give the prose versions a try? ;)

- Trey Causey

* While working on this article,

Flashback Universe friend Dr. K tipped us off to this interesting bit of Comic Book Sword & Sorcery trivia...

According to Roy Thomas, Gray Morrow had completed an adaptation of the Conan story "The Elephant Tower" for Timely, but the story was never published. As far as Roy knew, the original art had been destroyed. I don't know the exact dates for this, but it was some time in the 1950s.

Then, in the late 60s, Gil Kane got the rights to make Conan comics, and he was going to self-publish these in magazine format following His Name Is ... Savage in 1968. Savage, however, was a financial failure for many reasons, and Kane had to give up the enterprise. He did work with Roy to convince Stan Lee to pick of the license, though. But when it came time for Stan to assign the artist on the series, he picked John Buscema instead, because he felt that Kane was too valuable an artist to waste on a series that was probably going to fail.

Thank you Dr. K!

Today on Caine's Digital Comic Watch, we are happy to present to you an interview with one of the leaders of iPhone Comics Revolution, Emiliano Molina, creator of ComicZeal and ComicZeal Sync!

Today on Caine's Digital Comic Watch, we are happy to present to you an interview with one of the leaders of iPhone Comics Revolution, Emiliano Molina, creator of ComicZeal and ComicZeal Sync!

Does ComicZeal come with free content? How much?

Does ComicZeal come with free content? How much?

How long have you been reading comics?

How long have you been reading comics?

Kull

Kull Thongor

Thongor Such was not to be. Due to the vagaries of negotiation, Conan came through, and Thongor would sit on the sidelines until March 1973 with Creatures on the Loose #23, where he would begin flexing mighty thews and generally behaving in a Conan-esque manner. Ravenhaired Thongor became a red-head after a couple of appearances, perhaps to distance him visually from his barbaric forebearer. Only, presumably, his hair-dresser knows for sure. Thongor battled monsters and foul sorcery until Creatures on the Loose #29 (1974), when he lost the book to Man-Wolf. Several of his appearances were written by George Alec Effinger, whose 1986 cyberpunk novel, When Gravity Fails, won both the Hugo and Nebula awards. Gardner Fox, with a long history of comics work and sword and sorcery (with his barbarian, Kothar) would work on the run as well.

Such was not to be. Due to the vagaries of negotiation, Conan came through, and Thongor would sit on the sidelines until March 1973 with Creatures on the Loose #23, where he would begin flexing mighty thews and generally behaving in a Conan-esque manner. Ravenhaired Thongor became a red-head after a couple of appearances, perhaps to distance him visually from his barbaric forebearer. Only, presumably, his hair-dresser knows for sure. Thongor battled monsters and foul sorcery until Creatures on the Loose #29 (1974), when he lost the book to Man-Wolf. Several of his appearances were written by George Alec Effinger, whose 1986 cyberpunk novel, When Gravity Fails, won both the Hugo and Nebula awards. Gardner Fox, with a long history of comics work and sword and sorcery (with his barbarian, Kothar) would work on the run as well. Elric

Elric When Fafhrd and Gray Mouser came to comics, they did so in an unlikely place. They first appeared on the last panel of Wonder Woman #201, during her powerless, kung-fu-fighting, Diana Prince era. Issue 202 has them teaming up with Wonder Woman, her sifu I-Ching, and Catwoman, to thwart a wizard and save Jonny Double who’s trapped inside a mystic gem. In the words of Bart Simpson: “You can’t make this stuff up!”

When Fafhrd and Gray Mouser came to comics, they did so in an unlikely place. They first appeared on the last panel of Wonder Woman #201, during her powerless, kung-fu-fighting, Diana Prince era. Issue 202 has them teaming up with Wonder Woman, her sifu I-Ching, and Catwoman, to thwart a wizard and save Jonny Double who’s trapped inside a mystic gem. In the words of Bart Simpson: “You can’t make this stuff up!”