Welcome to day four of our continuing countdown of the best robots to grace the pages of comic books, where we break into the top ten.

10 - The Metal Men

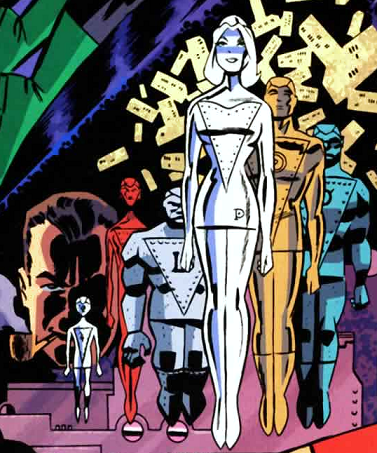

I believe, if we discount analogues, the Metal Men are the first theme-based superheroes to ever appear in comics. Today, some people might call them Toyetic, but I think that term is both vague and inexact whereas thematic is a better description of the Metal Men’s defining affinity to each other.

Created by Robert Kanigher and Ross Andru, the Metal Men used the metal-themed gimmick to give the team a bond that made them instantly identifiable to new readers as belonging to a team. With their similar uniforms and color coded bodies, any reader could look at a Metal Men comic and grasp the underlying structure of the team. This plays on a little quirk comic book readers have: we like to categorize things. The beauty of the Metal Men is they are already categorized for us!

With their introduction, theme-based teams have appeared many times in comics (several times in the Metal Men’s own comic.) Some are physical in nature, like The Gas Gang from Metal Men 6, while some some have a more abstract theme (Zodiac, Fathom Five, The Elementals, Serpent Society, etc. …)

The other thing that made the Metal Men unique (at DC as least) was that they were a team with members with very distinct personalities. Whereas the Justice League members all tended to act pretty much the same, the Metal Men gave us DC’s real first Marvel-like characters. Tin was cowardly, Mercury was a hothead, Lead was the lovable lunk head, Platinum was the girl (hey – it was the sixties, y’know?)

These two aspects proved so successful that the Metal Men got their own title in 1963 and ran bi-monthly until 1969. After that, their published presence would be spotty with a brief resurgence in 1976 which lasted until 1978 when their title became a victim of the DC Implosion.

Why didn’t the Metal Men fare better in the Bronze Age? I suspect partly because their original comic was a bit more campy or sublime than what readers were looking for in the ’70s. A reading of their later Bronze Age stories gives us more serious stories (as did their spots in Brave and the Bold.)

As of this writing, they were most recently retconned (for the third time) in the pages of New 52 Justice League 28. Still, I think attempts to “serious up” the Metal Men miss something. They aren’t really that type of team. I remember hearing a story about how Darwyn Cooke tried to sell DC on the idea of a Metal Men series he would write and draw but for whatever reason DC just wasn’t interested.

Now that the New 52 era is over and DC is looking around the publishing landscape for new projects, will we see the return for a light-hearted, comical Metal Men series? I sure hope so!

— Jim

9 - The Original Human Torch

First appearance: Marvel Comics #1 (October 1939)

Created by writer/artist Carl Burgos for Timely Comics (what would one day become Marvel), The Human Torch was one of the first super heroes to be dubbed an Android. The term Android had been become popular through it’s introduction via pulp science fiction, starting with Jack Williamson’s The Cometeers in 1936.

With his fiery frame and easy to grasp powers, The Human Torch became one of Timely’s most popular characters alongside Captain America and The Sub-mariner. This popularity lasted all through the Golden Age of comics, but dissipated by the 1950’s (when most superhero comics ceased publication). Unlike Cap or Namor, the original Human Torch was not seen in a Timely/Marvel comic again until he was revived in Fantastic Four Annual 4 in 1966.

With his fiery frame and easy to grasp powers, The Human Torch became one of Timely’s most popular characters alongside Captain America and The Sub-mariner. This popularity lasted all through the Golden Age of comics, but dissipated by the 1950’s (when most superhero comics ceased publication). Unlike Cap or Namor, the original Human Torch was not seen in a Timely/Marvel comic again until he was revived in Fantastic Four Annual 4 in 1966.Unfortunately, the original Human Torch would sacrifice himself in that FF Annual and vanish into the annals of Marvel history. Readers would have to wait until 1975 when Jim Hammond would come roaring back in not one, but two Marvel Comics: The Avengers and The Invaders.

In The Avengers, his return is limited to a mention of his android body being used by Ultron in the creation of the Vision. This plot point was developed by Neal Adams and Steve Englehart in Avengers 133-135, but I suspect that storyline ran counter to the plans of Roy Thomas as he plants the seeds for its undoing in What If...? 4 where he suggests that the Torch’s creator Professor Horton made a second android named Adam who was used for the construction of the Vision. However, John Byrne would later reaffirm the idea that at least some parts of the Human Torch were used to create the Vision in West Coast Avengers. In WCA 50, Jim Hammond is revived for good and becomes a permanent fixture in the Marvel Universe.

In The Invaders, The Human Torch fights in World War II alongside Captain America, Bucky, Sub-Mariner and Toro. I’ve written about my appreciation for this series numerous times. I consider it the best use of the character not only in the Bronze Age, but in any age of comics. To me, the original Human Torch works best in the era he was created. In the modern age, for better or worse, he’s a second rate Johnny Storm.

Which brings me to a point – in a way, the original Human Torch is essentially the lone member of the Marvel Universe’s answer to the Justice Society of America. He’s a legacy hero in a universe that doesn’t really have any others. I know what you’re thinking – “What about Captain American and the Sub-mariner?” I would say they don’t really count because they were both fully borne into the new age of Marvel at the very beginning. Unaged and unfazed by the passage of time, both Namor and Cap dive right into the new era of the Marvel Universe. Poor Human Torch wakes up to find himself replaced by a younger, cooler version and dies in his ’60s reintroductory tale. There is no Earth 2 All Winners Squad there to welcome him back to reality…

…instead, he just gets dismantled physically and metaphysically. What an unjust fate for such an historical character.

— Jim

8 - Shōgun Warriors

First appearance: Shōgun Warriors #1 (February 1979)

Go big or go home. Home, in this case, being Japan.

|

| Mazinger Z. |

Bandai subsidiary Popy made most of these toys, and they sold well, attracting the attention of American toymaker Mattel, who licensed as many as they could snap up for American distribution. Despite the various manga and anime these Super Robot toys were based on having no connection, Mattel marketed their American versions together under a single brand, one evocative of their Japanese origins: Shōgun Warriors.

|

| The stars of Shōgun Warriors as two-foot tall Jumbo Machinder toys. |

To promote the toys, Mattel enlisted Marvel Comics to create a Shōgun Warriors series. The "more-characters-more-More-MORE" approach that would dominate Transformers and G.I. Joe licensing lay in a few years in the future, so Mattel lent out only three of the robots to Marvel: Dangard Ace, Raydeen, and Combatra. In the comic, these giant robots were created by an alien religious order who enlisted an international team of human pilots to operate them: stuntman Richard Carson from the U.S. for Raydeen, test pilot Genji Odashu from Japan for Combatra, and ocean researcher Ilongo Savage for Dangard Ace.

|

Featuring the final fate of three

unexpected guest stars.

|

Curiously enough, Moench and Trimpe were putting out Marvel's other Japanese licensed book concurrently with Shōgun Warriors: Godzilla. While the Shōguns never met Godzilla, that title did introduce a giant robot much like them whom Marvel owned outright, Red Ronin. And Trimpe gave us this undeniably awesome iron-on patch, which is made all the more mind-blowing when you realize the characters America tossed together cavalierly would be all-star line-up of individual heavy-hitters in their native Japan:

— Scott

7 - The Sentinels

First appearance: X-Men #14 (November 1965)

|

| Hulking, but not yet giant. |

|

| Bigger: The Master Mold. |

Sentinels rarely survive more than one encounter with the X-Men, with two notable exceptions.

|

| Worse than a zombie: a robot zombie. |

|

| Nimrod at left, Bastion at right. |

Time will tell what future forms the Sentinels take, but one assumption seems safe: They'll always return to form as implacable enforcers of prejudice, carrying out their terrifying orders long after their human masters are gone.

— Scott

6 - Machine Man

First appearance: 2001: A Space Odyssey #8 (July 1977)

The robot known as Machine Man has been in every corner of the Marvel Universe — and a few outside of it.

In the late 1970s, Jack Kirby returned to Marvel after jumpstarting the Bronze Age at DC with titles such as The New Gods, Kamandi, The Demon, and The Sandman. Creatively, he was on fire — pumping out new concepts in rapid succession and absorbing, digesting, and putting the zeitgeist to paper with uncanny potency. Like a shaman reading entrails, he recombined words and concepts from Popular Science and popular paranoia into surprising prophecies about the future, little realizing many of them would come to pass (in less bombastic form) over the next couple of decades.

|

| Not really set in the Marvel Universe. |

When 2001 #8 introduces a robot soldier program, your first instinct as a reader is to assume it's in the near future of the 21st century, where so much of 2001 the comic takes place. It's a world of super-technology, where the government is in the midst of shutting down a project to turn thinking computers into soldiers. (For Kirby, Captain America seems the next logical step from the HAL-9000.) They're rounding up and shutting down the X series of robots they've created, but one isn't at the facility. Dr. Abel Stack has taken it home with him, where's he given it a prosthetic human face and ignored its serial number designation "X-51"; he's calling it "Aaron" — and "son." Rather than see Aaron destroyed, Dr. Stack removes the explosive failsafe within his body and sacrifices himself to give Aaron a head start running from government forces. When Aaron finds his way into the outside world and meets ordinary people from different walks of life, it becomes evident the world of this issue is not the world of the near future but of the then-present. Aaron (or "Mister Machine," as he takes to calling himself) encounters the monolith once or twice before 2001 is unceremoniously canceled — and replaced with a new title, Machine Man, starring the erstwhile Mr. Machine.

|

| Set squarely in the Marvel Universe. |

DeFalco returned to Machine Man in 1984, once Marvel had begun publishing short-run limited series, with a four-issue mini set in the far future of 2020. An early cyberpunk comic, this incarnation of Machine Man featured artwork from Herb Trimpe and Barry Windsor Smith.

Since then, Machine Man has been Marvel's robot ronin — tied to no book or direction in particular, wandering wherever trends and publishing strategies take him. He spent time pining over Jocasta, then fought alongside and against the Avengers before being made over as a Sentinel and ending the 20th Century with own title in the X-Men extended family.

For that, of course, he returned to using the monicker X-51. Although the title was short-lived (as part of the equally short-lived M-Tech line), writer Karl Bollers used it to explore issues of personhood and agency in a science-fiction setting Machine Man hadn't enjoyed since his 2001 days. An overlooked gem, X-51 even reconnects Machine Man to the monolith, which Bollers deftly ties to the Celestials, characters who originated in — drumroll please — Kirby's Eternals.

More sidelong déjà vu awaited Machine Man in his next starring role. Ditching both his serial number and his super-heroic identity in favor of a long coat and being called simply "Aaron," Machine Man became an anchor of Warren Ellis and Stuart Immonen's Nextwave: Agents of H.A.T.E. Relentlessly cheeky and subversive, Nextwave took place outside the mainstream Marvel Universe, or at least that's what Ellis said at the time. The claim was consistent with the company's fractured publishing strategy of introducing new, different, and often contradictory visions of the Marvel Universe, from the Ultimate Universe to various Max titles to Marville to Megalomanical Spider-Man and Incorrigible Hulk to the notorious Trouble. When "Civil War" repositioned line-wide continuity as a priority at Marvel, Aaron's extra-Marvelous adventures in Nextwave became canonized, and the updated version of Machine Man found himself working with the 50-State Initiative.

In recent years, he's reunited with Jocasta and found a new role as a fighter of Marvel Zombies (the variant-cover kind, not the fanboy kind). It's a curious about-face from the snark of Nextwave, a pivot from deep ironic distance to fighting nihilism. But, as we see from a quick glance over his history, it's hardly the most drastic turn Aaron/X-51 has taken. He's even reclaimed the name "Machine Man."

— Scott